- Details

- Written by Kevin P. Feehan

- Category: Legal

This article was originally published in the Fall 2014 issue of The Catholic Dimension, and is re-posted here for public reference.

Introduction

Any young Canadian girl or boy who has attended a National Hockey League game in Canada has sung the words “God keep our land” as part of the National Anthem.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms opens with the words:

“Whereas Canada is founded upon principles that recognize a supremacy of God and the Rule of Law”,

and that Charter contains the basic guarantee of religious freedom in section 2 (a):

“Everyone has the following fundamental freedoms:

(a) Freedom of conscience and religion . . .”

In Canada, there is no official constitutional separation of church and state. The Supreme Court of Canada said in Big M Drug Mart [1985]:

“A truly free society is one which can accommodate a wide variety of beliefs, diversity of tastes and pursuits, customs and codes of conduct.”

Canadian constitutional law therefore promotes the active engagement of a diversity in religious views, the promotion and respect of all religious views in relationship to one another; it promotes a religious pluralism, not the absence of religion in state matters, but the encouragement of a diversity in religious views, practices, beliefs and observances as part of a Canadian state.

Religious Pluralism

When one speaks of religious pluralism, in the context of constitutional law, one envisions not merely diversity of religion or faiths but the active engagement, not merely tolerance, of such diversity, the active seeking of understanding of religious differences “not in isolation, but in relationship to one another”.

In this context, religious pluralism is neither relativism, or normative pluralism, the philosophy of Quebec’s “secular revolution”, the belief that every spirituality is equal and no faith gives access to absolute truth, nor syncretism, the amalgamation of faiths, creeds and spiritualties, blended together as a shopping cart of spiritual understandings. Religious pluralism means allowing each believer their own religious identity, and their own religious commitment, but provides for the encounter of those commitments, holding religious differences not in isolation but in relationship. It is based on encounter, understanding and dialogue, examination and self-examination.

Chris Beneke in Beyond Toleration: The Religious Origins of American Pluralism, 2006, says that religious pluralism goes beyond toleration, because toleration is only the absence of religious persecution, and does not necessarily preclude discrimination; it is defined as “respecting the otherness of others: and accepting the given uniqueness endowed to each one of us” (Beneke, 2006). Mark Silk in Defining Religious Pluralism in America: A Religious Analysis (2007) says that “it is a cultural construct that embodies some shared conception of how a country’s various religious communities relate to each other and to the larger national whole”, and involves dialogue between persons of different faiths, denominations and experiences for the goal of reducing conflict and achieving mutually agreed upon ends. Such pluralism entails “not competition but cooperation”, both inter and intra religious groups.

The Canadian constitution, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and Canadian case law attempts, not always successfully, to achieve a goal of religious pluralism, allowing each Canadian, individually, to practice their spirituality and faith, while recognizing, respecting and encouraging others to do the same, even though differently, as a different interpretation or path to the same end. This concept attempts to allow each individual to hold their own personal beliefs sacrosanct, while appreciating and respecting those of others.

A significant example of this religiously plural intent in the Canadian constitution is found in section 93(1) of the Constitution Act, 1867:

“In and for each Province the Legislature may exclusively make Laws in relation to Education, subject and according to the following provisions:-

(1) Nothing in any such Law shall prejudicially affect any right or privilege with respect to Denominational Schools which any Class of Persons have by Law in the Province at the Union”.

It is generally agreed that Confederation would not have been achieved in Canada without the protections accorded to denominational or separate schools that were forged largely by D’Arcy McGee in 1864 and Alexander Galt in 1866. The most often quoted excerpt to this effect is the speech in the House of Commons of Prime Minister Sir Charles Tupper in 1896:

“...I say it within the knowledge of all these gentlemen ... that but for the consent to the proposal of the Hon. Sir Alexander Galt, who represented especially the Protestants of the Great Province of Quebec on that occasion, but for the assent of that conference to the proposal of Sir Alexander Galt, that in the Confederation Act should be embodied a clause which would protect the rights of minorities, whether Catholic or Protestant, in this Country, there would have been no Confederation .... I say, therefore, it is important, it is significant that without this clause, without this guarantee for the rights of minorities being embodied in that new constitution, we should have been unable to obtain any confederation whatever” (Debates of the House of Commons, March 3, 1896, col. 2719-2724).

That provision which applies in Ontario, was modified for Manitoba by the Manitoba Act, 1870, for Alberta by the Alberta Act, 1905 and for Saskatchewan by the Saskatchewan Act, 1905. It applied in Quebec until 2000 when it was removed by constitutional amendment. A similar provision as set out in Newfoundland’s Terms of Union applied until 1998, when also removed by constitutional amendment. It remains protected in section 29 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms:

“Nothing in this Charter abrogates or derogates from any rights or privileges guaranteed by or under the Constitution of Canada in respect of denominational, separate or dissentient schools.”

Distinction from the American Approach

The American Constitution, as it addresses fundamental rights, is based interpretively on the words in the Declaration of Independence, July 4, 1776:

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their creator with certain unalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuant of happiness.”

Life, liberty and the pursuant of happiness are all individualistic rights, granted to persons, enforceable by persons on an individual basis.

On the other hand, the animating words, describing the powers of the Canadian federal government in section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867, are:

“It shall be lawful for the Queen, by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate and House of Commons, to make Laws for the Peace, Order and Good Government of Canada...”.

Peace, order and good government are collective rights, possessed by all of the peoples of Canada, commonly in a federal system.

The First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, the “separation of Church and state” pronouncement, reads in part as follows:

“Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, nor prohibiting the free exercise thereof...”.

The United States Supreme Court in Thomas v. Indiana Employment Review Board, 450 US 707 (USSC, 1981) in interpreting these American constitutional provisions adopted a subjective, personal and deferential definition of freedom of religion, centered upon sincerity of belief:

“The guarantee of free exercise is not limited to beliefs which are shared by all of the members of a religious sect ....Courts are not arbiters of scriptural interpretation” ( quoted in Syndicit Northcrest c. Amselem, para. 45).

A similar conclusion was reached in Frazee v. Illinois Dept of Employment Security, 489 US 829 (US Ill. S.C., 1989).

Canadian Religious Pluralism is different than the American Separation of Church and State

As a result, the Supreme Court of Canada has indicated in Big M Drug Mart Ltd. [1985] 1 S.C.R. 295, that “recourse to categories from the American jurisprudence is not particularly helpful in defining the meaning of freedom of conscience and religion” in Canada (para. 105).

The Supreme Court of Canada addressed the distinction between the American constitutional protection in the area of conscience and religion and that given by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms in R. v. Videoflicks Ltd. (“Edwards Books”), [1986] 2 S.C.R. 713 where it acknowledged: “the difference between the Canadian and American constitution is not just in respect of the wording of the provisions relating to religion, but also regarding the absence of a provision such as s. 1 of the Canadian Charter in the American instrument” (para. 86). It acknowledged that when strictly read, the American Constitution asserted “that First Amendment rights were absolute, that is, not subject to the sort of balancing which is undeniably required in Canada under s. 1 of the Charter “ (para. 93), even though in addressing freedom of religion arguments in the United States, the Supreme Court there “was engaged in the balancing process which, under a constitution like Canada’s, would properly be dealt with under a justificatory provision such as s. 1” (para. 94).

The importation of American, individualistic fundamental freedoms which are absolutist in nature, do not have a “justification” exception, and are based upon an express separation of church and state, are therefore difficult to transport into a Canadian understanding, which is traditionally collective in nature, subject, however, to a degree of individualization expressed in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, but modified by a justification for breach of rights in section 1 of the Charter, without an express provision of separation of church and state, and based upon an historic religiously plural experience and intent.

Conclusion

Canadian society, informed by the Canadian constitution, is one which values tolerance, multiculturalism, respect for minorities and respect for both collective and individual rights. Canadian emphasis on religious pluralism, encouraging and respecting a diversity of religions or faiths and active engagement in understanding of religious differences is reinforced by the constitutional text and case law interpretations. Religious pluralism entails cooperation and understanding between religious denominational groups, respect for and encouragement of beliefs, and the holding of those religious differences in relationship. Religious rights in Canada are a product of Canadian legal sociology, the addition of individual rights and protections in sections 2 through 15 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, as modified and balanced by the “justification” section, section 1, and the attempt of the courts in this country to respect "sincere belief” without engaging the secular courts in the quagmire of “validity” of religious beliefs. That is the quintessential Canadian way.

- Details

- Written by Kevin P. Feehan

- Category: Legal

This article was originally published in the Fall 2004 issue of The Catholic Dimension, and is re-posted here for public reference.

Catholic separate school rights are constitutionally protected by virtue of s. 93(1) of the Constitution Act, 1867, section 17(1) of the Alberta Act, 1905 and section 29 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The provisions of the School Ordinance, 1901, make it clear that at the time Alberta entered Confederation, Catholic separate ratepayers, now electors, had the right to establish Catholic separate school districts, and that once established, the trustees of that district had all of the "rights, powers, privileges and... liabilities" as set out with respect to public school districts, including the right to: engage and dismiss teachers; impose duties and obligations upon teachers; ensure that the schools operated according to the provisions of the School Ordinances, including those provisions protecting denominational education.

In order for a constitutional right to preferential hiring, promotion and denominational dismissal for cause to be protected, it must have been a right enjoyed by Catholic separate ratepayers by law at the time Alberta entered Confederation, and that right must relate to denominational education, or non-denominational aspects necessary to delivery of the denominational aspects of education. See PSBAA v. Alberta [2000], OECTA v. Ontario [2001], A.G. of Quebec [1991], and Ottawa Separate School Trustees v. Mackell [1917].

If these criteria are met, denominational education rights will be a defence to the enforcement of the provisions of the Human Rights, Citizenship and Multiculturalism Act and ss. 2(a) and 15 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms as against a Catholic board.

Courts in Canada have unanimously agreed in Brophy v. A.G. of Manitoba [1895], Tiny Separate School Trustees v. The King [1927], Caldwell v. Stuart [1984], Daly v. Ontario A.G. [1997], and Hall v. Powers [2002], that Catholic education has a distinct Catholic denominational philosophy which fundamentally recognizes the duty of the Catholic Church to focus upon the formation of the whole person, according to the doctrine of the Catholic Church, attempting to achieve a synthesis of faith and culture fully permeated with the spirit and meaning of the gospel. The purpose and mission of a Catholic separate school is the inculcation of Catholicism in every aspect of the school, not simply in religion class, and the Catholic school that does not provide such a denominationally-focused education may be deprived of its separate school status. See Jacobi v. Aqueduct RCSSD No. 374 [1994].

Given this very distinct role of Catholic education, it is not surprising that the role of the teacher in the Catholic school is to emulate by personal example and modeling the teachings of the Catholic Church. In the Catholic philosophy of education, the teacher is required to live in "imitation of Christ" and to be a constant example of the teachings of the Church, not only in their words but in their conduct. They are required to be the "highest model of Christian behaviour" and to transmit the Catholic faith to their students through their personal example, beliefs, values, attitudes and lifestyle. It is this expectation which is incorporated in the contractual relationship between the teacher and the Catholic board, requiring that the teacher follow, both in and out of school, a lifestyle and deportment in harmony with Catholic teachings and principles. See Caldwell, supra, and Daly, supra.

It has been clear since the earliest days of Confederation that Catholic separate schools are entitled to preferential hiring; that is, the preference to hire Catholic teachers over others and the preference to require all teachers to live as examples of the Catholic faith. The Courts have found that such a preferential hiring right was in existence at the time of Confederation and has been legally recognized throughout history. More recently, the Courts have recognized the right of Catholic separate schools to terminate the employment of teachers for "denominational cause," including marrying in a civil rather than a Church ceremony, marrying a divorced person, or engaging in pre-marital sexual intercourse, as evidenced by requests for maternity leave. In addition, the Courts have recently recognized the right to preferential promotion of teachers to the positions of principal, vice-principal or departmental heads, on the basis of Catholic preference, if the promotion policy was a specific religious requirement necessary to maintain the denominational character of the school. See Re Essex RCSSB and Porter et al [1978], Caldwell, supra, Re Daly, supra, OECTA v.Dufferin-Peel RCSSB [1999], and Re Casagrande and Hinton RCSSD No. 155 [1987].

The standard to which a teacher in a Catholic school will be held is an elevated standard of Christian behaviour and requires attentive compliance in all aspects with Catholic teachings and principles. We live in a society in which others may behave in ways not always in strict communion with Catholic theology and doctrine. Teachers in Catholic schools are not expected to permit such relaxations of standards. They are held to a higher standard, not necessarily fair by societal comparison, but fundamental to the permeation of Catholic teaching in the Catholic school.

Where there has been a direct conflict between the provisions of human rights legislation, or sections 2(a) and 15 of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, with denominational education rights preserved by section 93(1) of the Constitution Act, 1867, and section 17(1) of the Alberta Act, 1905, the Courts have resolved that conflict in favour of upholding denominational education rights, relying on section 29 of the Charter and the "special treatment guaranteed by the Constitution to denominational, separate or dissentient schools" even where those rights currently fit uncomfortably with other Charter guarantees. See Re Casagrande, supra, Mahe v. Alberta [1990] and An Act to Amend the Education Act (Bill 30) [1987].

Finally, the Courts have held that the constitutional rights enjoyed by separate Catholic schools are not frozen "as at 1905," but as educational modes and methods evolve, so do such rights. As a result, the recent phenomenon of reliance upon teacher assistants and other non-teachers in the classrooms, as an extension of mode or method of instruction in the classrooms, attracts the constitutional protections relevant to teachers as they existed in 1905. See Ottawa Separate School Trustees v. City of Ottawa [1915], Hirsch v. Protestant School Commission of Montreal [1928], Jacobi, supra, Ontario Home Builders' Assoc. v. York Region Board of Education [1996], OECTA v. Ontario, supra, and Bill 30, supra.

- Details

- Written by Kevin P. Feehan

- Category: Legal

This article was originally published in the Spring 2005 issue of The Catholic Dimension, and is re-posted here for public reference.

The first formal European education to reach what is now Alberta arrived with the Catholic missionaries. In 1838, Fathers Blanchet and Demers arrived at Fort Edmonton, in 1842, Father Thibault founded the first Catholic mission at Lac St. Anne and was joined in 1844 by Father Bourassa, who later founded missions at Lesser Slave Lake and Grande Prairie. In 1845, Father de Smet resided in Edmonton while he acted as "peace maker" between the Blackfoot and the Flatheads. These Oblate fathers were joined in 1853 by Father Remas and each were involved in the introduction of Catholic education in what is now Central and Northern Alberta. However, the first missionary to introduce formal schooling was Father Albert Lacombe who arrived at Lac St. Anne in 1852 and immediately began instructing both adults and children.

In 1857, Bishop Tache founded a native school at Lac la Biche, under the control of three Grey Nuns-Sisters Grienette, Daunais and Trisseur. By 1859, three other Grey Nuns, Sisters Leblanc-Emery, Lamy and Jacques-Alphonse, had arrived at Lac St. Anne and the first boarding school, with 42 students, was opened. That allowed Father Lacombe and Father TachŽ to establish a mission in St. Albert in 1861.

The first regular school west of the Red River Colony was established at Fort Edmonton in 1862 by Brother Scollen, soon followed by the normal schools in St. Albert in 1863, under the tutelage of Father Grouard, Brother Alexis and a number of teaching sisters from Lac St. Anne, and in Fort McLeod in 1863.

In the 1860s, the separate school question was a prominent issue in the political debate leading to confederation, which could not have been achieved without the protections granted to separate schools in Section 93 of the Constitution Act, 1867. Section 93 conferred on the provinces the exclusive power to make laws in relation to education. However, it was the D'Arcy McGee amendment of 1864 and the Alexander Galt amendment of 1866, embodied in subsections 1 through 3 of Sections 93, which was recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada in Reference re: Bill 30 as the political compromise, the "solemn pact," "which made confederation possible." As Sir Charles Tupper said in the House of Commons:

" ... without this clause, without this guarantee for the rights of minorities being embodied in that new constitution, we should have been unable to obtain any Confederation whatever ... "

On June 23, 1870, Rupert's Land and the Northwest Territories became part of the Dominion of Canada and shortly thereafter the Northwest Territories Act, 1870 was passed.

Upon addition of Rupert's Land and the Northwest Territories to the Dominion of Canada, a report was prepared on education in the new area by Bishops Tache and Grandin. They reported that by June 1871, there were five elementary schools in full-time operation, and 15 missionary priests and nuns providing education in those schools.

In 1875, the second Northwest Territories Act established formal state-sponsored education in the area that is now Alberta. It provided that the majority of the ratepayers of any district or portion of the Northwest Territories could establish a public school and that the minority of ratepayers, whether Protestant or Catholic, could establish separate schools in the same area. The 1875 Act specifically provided that the ratepayers establishing the Protestant or Roman Catholic Separate Schools would be liable only to such taxation as they imposed upon themselves and would not be liable for taxation with respect to public schools.

The first year that the Government allocated money for education in the Northwest Territories was 1878 and the total financial allocation in that year for all schools in the territories was $2,000.

Although there had been an attempt to establish a public school at Fort Edmonton in 1874 and 1875, the first formal public school with any permanent status was founded in 1880 and the first public school grant in the area that is now Alberta was made in 1881, 30 years after the foundation of the first formal Catholic schooling in the area by Father Lacombe.

The first permanent Catholic school building was constructed in Edmonton in 1882 as an appendage to St. Joachim's Church. By 1882, Catholic boys and girls schools in St. Albert had an enrollment of between 60 and 70 pupils daily. In 1883, Frank Oliver, the founder of the Edmonton Bulletin and a member of the Northwest Territories Assembly, introduced the first Schools Ordinance to provide for the formation of school districts in the Northwest Territories as had been contemplated by the Northwest Territories Act, 1875. In 1884 Catholic public school districts numbers one through seven were formed in what was to become Alberta and Saskatchewan. By 1884, the St. Albert school had founded three satellite schools in the surrounding areas. In 1885, Fort Saskatchewan Roman Catholic Public School District No. 2 and St. Albert Roman Catholic Public School District No. 3 were officially organized.

These were the years of the first Riel Rebellion in the Northwest Territories and they were also the years that the Sisters of the Faithful Companions of Jesus (F.C.J.) arrived in Alberta to take over many of the responsibilities of Catholic education in the province.

In 1885, the F.C.J. had been serving both the forces of Riel and the government in the central theatres of the war-Prince Albert, St. Lawrence, St. Anthony's and Batoche. In July 1885 they were moved by Bishop Grandin to the relative safety of Fort Calgary and opened a school for 20 Metis children on September 1. The Lacombe (now Calgary) Roman Catholic Separate School District No. 1 was established under the directorship of Mother Grieve on December 18, 1885.

In 1888, the mission school of St. John the Evangelist was opened in Stony Plain and on October 4, 1888, St. Joachim (now Edmonton) Separate School District No. 7 was formed. In April 1889, St. Aloysius Catholic School in Lethbridge was established and in 1890 the F.C.J. arrived there as well to take charge of its 57 students.

In 1889 the mission school in Hobbema was opened, in 1892 the Thibault Roman Catholic Public School District No. 35 in Morinville was officially organized, and the native school at Saddle Lake was established with Father Grandin as its first principal. In 1894, St. Anthony's Separate School District No. 12 was formed to provide Catholic education in the Village of Strathcona in what is now south Edmonton. By 1894, the school at Edmonton taught 137 pupils and had a staff of three teaching sisters.

The earliest existing Territories curriculum dates from the year 1894. In that year the public curriculum covered reading, writing, arithmetic, spelling, grammar, geography and history. The Catholic schools taught those subjects and added French, ethics, calisthenics, literature, composition, drawing, object lessons, bookkeeping, needlework, music, and kindergarten, and, of course, religious education.

In 1896, the Vegreville Roman Catholic Public School District No. 44 was established. By 1901, school exhibitions and contests had become popular in the Northwest Territories. That year, 13 of the 18 prizes awarded in the Northwest Territories, for free-hand mapdrawing and writing, were received by Catholic school students, nine by students attending St. Joachim Catholic Separate School in Edmonton and four by students attending St. Albert Public Catholic School. In 1903, St. Joachim's took first prizes in every area of competition-mapmaking, object and crayon drawing, writing, collection of wild flowers and noxious weeds.

In 1904 and 1905, the Country, and particularly the Northwest Territories, was consumed by the move to create provinces out of the areas that are now Alberta and Saskatchewan. Crucial to that political process was determining the rights of separate schools in the Northwest Territories and those rights were specifically addressed in s. 17 of the Alberta Act and the Saskatchewan Act, 1905.

The legislative process of settling upon the wording of s. 17 of the Alberta Act was contentious and led to the Northwest Schools Crisis of 1905, which very nearly resulted in the fall of the Laurier government. Justice Minister Sir Charles Fitzpatrick, who later in his role as Chief Justice of Canada, delivered the majority decision on separate school rights in the Gratton case, wrote a number of the 11 drafts of s. 17, assisted by Monsignor Sbaretti and Sir Clifford Sifton. This fundamental constitutional protection established the principles of separate school education that we enjoy today-proportionality in the distribution of public monies in the form of grants, taxes and other public funds, the right of access to the municipal taxation base, non-discrimination, equity and fairness as related to the operation and maintenance of separate schools, and the right of full control and management of the schools as it affects all denominational and necessary non-denominational aspects of the schools, including the right of full permeation of Catholic teachings.

The Alberta Act accomplished those fundamental principles by constitutionalization of the rights and privileges accorded separate school supporters in chapters 29 and 30 of the Ordinances of the Northwest Territories, 1901.

Chapter 29, the School Ordinance, set out as some basic privileges the right to establish a separate school district, to set such mill rates as the ratepayers determined to impose upon themselves and to levy assessments upon the ratepayers of the separate school district, the right not to be liable to assessments levied by any party other than the separate school district; the ability to exercise all rights, powers, privileges and be subject to the same liabilities and methods of government as provided with respect to public school districts and the right to expand the boundaries of the separate school district, by Ministerial Order, provided that it was for the benefit of separate school electors and would not prejudice those involved.

Chapter 30, the School Assessment Ordinance, set out specific mechanisms for the exercise of the right or privilege to levy and collect or requisition and receive taxes upon the properties of separate school ratepayers, to access that proportion of individual taxes as declared with respect to jointly held properties, and to access corporate taxes.

Perhaps the best explanation of the rationale behind early Catholic education in the Province of Alberta is expressed by local historian, Dr. David Hall, and by philosopher, Van Cleve Morris. Dr. Hall said the following about the radically divergent denominational underpinnings of separate and public schools in the Northwest Territories and Alberta during this period:

"The philosophy of Catholic education was not compatible with the philosophy of Protestant education during the period on which my study focused (late 19th - early 20th centuries). For a Catholic, religion was the central concern of life: the prism through which life was to be viewed; or, to use another analogy, the centre around which the right of life properly should revolve. This of course meant religion as interpreted by the Roman Catholic Church, which had been established by God to help mankind to live their lives as preparation for an eternal destiny. The Church must therefore control the education of a Catholic child, so that all aspects of education could be taught within the context of this religion centred perspective. Protestants believed, generally speaking, that religion could be separated from the educational curriculum. Protestants were no less committed to the ideal of a God-centred life, but because of denominational divisions among Protestants, and between Protestants and Catholics, no commonly agreed upon religious view could lie at the centre of education. Hence the Protestant schools preferred to take a "neutral" position on many moral and theological issues because of this diversity of beliefs. (Parenthetically, it should be noted that there was at the time an overwhelming Christian consensus in society; professing non-Christians of any description were a tiny minority. Thus the public schools were, in most cases, in effect Protestant schools.) Such religious education that did take place in the Protestant schools-morning prayers, a brief Bible reading, possibly a half hour of religious instruction at the end of the school day-were substantially separated from the "secular" subjects of study in the school. Most Protestants believed that the proper place for religious education was in the church, the Sunday school and the home. Both Protestants and Catholics viewed the publicly-funded schools as important instruments for socializing children. The notion that religious truth was subject to individual or denominational interpretation was implicit in the Protestant system, which made that system anathema to Catholics and the notion that the Catholic Church had a monopoly on the interpretation of truth was equally anathema to Protestants."

Van Cleve Morris underlined the theory of denominational permeation of the Catholic education of the day when he said that the teaching of morality in these schools:

"... appears, for example, in the affairs of the playground, in the kind of sports that are favoured and opposed, and in the code of sportsmanship by which the young are taught to govern their behaviours. It appears in the school's definition of the delinquent and in its mode of dealing with him ... It appears in the department of science: in the methods the young are expected to adopt in conducting their experiments ... It appears in the department of social studies: in the problems that are chosen ... in the manner in which they are discussed ... It appears in the department of literature: in the novels, in the poems, the dramas that are chosen for study, in what is considered good and what is considered bad ... It appears in the organization and the government of the school ... It appears in the program for the general assemblies of the schools: in the various leaders from the community ... It appears in the way the community organizes to conduct its schools: in the provision it makes in its school grounds, buildings, and equipment, in the kind of people it chooses to serve on the school board, and in the relation of the members of the board to the ... teaching staff."

In retrospect, one century later, it is this history and this philosophy of education, which has fashioned, formed and informed Catholic education today. It is upon this foundation that we forge the Catholic education of the next century.

- Details

- Written by Kevin P. Feehan

- Category: Legal

This article was originally published in the Spring 2014 issue of The Catholic Dimension, and is re-posted here for public reference.

In the Legally Speaking article published in the fall edition of the Catholic Dimension, we explored the concept of freedom of conscience and religion as guaranteed in section 2(a) of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms and reviewed a number of the primary cases addressing both freedom of religion and freedom of conscience in Canada.

However, in Canada such freedoms are not absolute. They are moderated and balanced as against the “collective good” by the justification provisions of section 1 of the Charter, which both guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in the remaining sections of the Charter and constrains them to reasonable limits expected in a free and democratic society:

“1. The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms guarantees the rights and freedoms set out in it subject only to such reasonable limits prescribed by law as can be demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society.”

Legal proof pursuant to section 1 is divided into two criteria justifying the breach of other sections of the Charter: the “reasonable limits prescribed by law” requirement and the “demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society” criteria.

On the “reasonable limits prescribed by law” portion of section 1, the party wishing to rely upon justification for the breach of a Charter right, must show that the provisions of the imposed law are “reasonably accessible to those which it affects”, precise in that they enable those whom it affects to regulate their conduct pursuant to the law, are not vague, in that they provide a sufficiently clear standard, and are a proper exercise of discretion, in that the discretion granted by the law is appropriately constrained by legal standards (Canadian Federation of Students v. Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority, 2009 S.C.C. 31).

Further, a section 1 Charter defence requires proof on the “demonstrably justified in a free and democratic society” portion of section 1 that the provisions of the law are pressing and substantial, that the means employed in the law are rationally connected to that objective, minimally impair the rights of those which it adversely affects and produce salutary effects which outweigh the deleterious effects of a breach (R v. Oakes, [1986] 1 S.C.R. 103, and Dagenais v. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, [1994] 3 S.C.R. 835).

The leading case on the application of “justification” pursuant to section 1 of the Charter, of a breach of the guarantee of freedom of conscience and religion under section 2(a) of the Charter is Hutterian Brethren of Wilson Colony v. Alberta, [2009] 2 S.C.R. 567. In that case, the Province of Alberta required that all driver’s licenses should have a photograph of the driver, which photograph would be kept in the province’s facial recognition databank for the purposes of identification and prevention of identity theft. The members of the Wilson Hutterite Colony objected to having their pictures taken on the basis that it offended the second commandment:

“You shall not make for yourself a graven image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above” (Exodus 20:1-17, RSV).

The most comprehensive discussion of the section 2(a) guarantee of freedom of religion in this case came in one of the dissenting decisions, that of Madam Justice Abella:

“Freedom of religion is a core, constitutionally protected democratic value. To justify its impairment, therefore, the government must demonstrate that the benefits of the infringement outweigh the harm it imposes”.

Justice Abella said, however, that there were circumstances where “the nature of the particular religious duty brings it into serious conflict with countervailing and competing social values and imperatives” requiring that “religious freedoms (be) subject to such limitations ‘as are necessary to protect public safety, order, health, or morals or the fundamental rights and freedoms of others...’.” In allowing for some impairment of the rights to conscience and religion, she said:

“’The values that underlie our political and philosophic traditions demand that every individual be free to hold and to manifest whatever beliefs and opinions his or her conscience dictates, provided ... only that such manifestations do not injure his or her neighbours or their parallel rights to hold and manifest beliefs and opinions of their own’ (quoting from Big M Drug Mart).”

Justice Abella said that both individual and group aspects of freedom of conscience and religion were important to consider, including “the right to manifest one’s religion in community with others”. This recognition that freedom of conscience and religion is both individual and communal was concurred in by the majority of the Court which quickly found that the Hutterian Brethren’s rights to freedom of religion had been infringed given that they sincerely held “a belief or practice that has a nexus with religion; and ... the impugned measure interferes with (their) ability to act in accordance with (their) religious beliefs in a manner that is more than trivial or insubstantial”.

However, the majority decision, in applying the Oakes/Dagenais test set out above, found:

“The goal of minimizing the risk of fraud associated with driver’s licenses is pressing and substantial. The limit is rationally connected to the goal. The limit impairs the right as little as reasonably possible in order to achieve the goal; the only alternative proposed would significantly compromise the goal of minimizing the risk. Finally, the measure is proportionate in terms of effects: the positive effects associated with the limit are significant, while the impact on the claimants, while not trivial, does not deprive them of the ability to follow their religious convictions”.

As a result, the limits placed on the Hutterian Brethren’s freedom of religion by the requirement to be photographed if they wished to hold a driver’s license, was “justified” under section 1 of the Charter.

Another case before the Supreme Court of Canada which addressed section 2(a) protection but justified a breach of freedom of conscience and religious rights by reference to section 1 was Whatcott v. Saskatchewan Human Rights Tribunal, 2013 SCC 11. In that case, Mr. Whatcott distributed flyers in Regina and Saskatoon targeting homosexuals. The Saskatchewan Human Rights Commission determined that the material “promoted hatred against individuals because of their sexual orientation”. One of the defences raised was freedom of religion, on the basis that:

“objection to same-sex sexual activity is common among religious people. They object because they believe this conduct is harmful; and many religious people also believe that they are obligated to do good and warn others of the danger”.

The Supreme Court of Canada dealt with the freedom of religion argument briefly. They said that “the protection provided under s. 2(a) should extend broadly”, that the “Court has consistently refrained from formulating internal limits to the scope of freedom of religion in cases where the constitutionality of a legislative scheme was raised”, found that the claimant sincerely held a belief or practice that had a nexus with his religion, and that the Human Rights provision interfered with Mr. Whatcott’s ability to act in accordance with his religious beliefs, which interference was more than trivial or insubstantial. As a result, the Court found a breach of the guarantee of conscience and religion and turned to the section 1 “justification” analysis.

Applying the Oakes/Dagenais test set out above, the Supreme Court of Canada found that the breach of this fundamental freedom was justified, recognizing that “s. 1 both guarantees and limits Charter rights”, and in the present circumstances:

“it does not matter whether the expression at issue is religiously motivated or not. If, viewed objectively, the publication involves representations that expose or are likely to expose the vulnerable group to detestation and vilification, then the religious expression is captured by the legislative prohibition”.

A similar result was reached by the Supreme Court of Canada in Multani c. Marguerite-Bourgeoys (Commission scolaire), [2006] 1 S.C.R. 256 where a Sikh boy was initially prohibited from wearing a kirpan in public school. The Court acknowledged that an absolute prohibition of a mandatory religious requirement was a breach of the section 2(a) guarantee of freedom of religion, that his belief was sincere and that the infringement was neither trivial nor insignificant. The issue then turned to whether the prohibition was justified under section 1. The Court found that the school boards’ object to provide a safe and secure school environment was pressing and substantial, and the prohibition against the wearing of a kirpan had a rational connection with that object, but that the absolute prohibition against wearing a kirpan did not minimally impair the student’s right as it stifled the promotion of values, multiculturalism, diversity and the development of an educational culture respectful of the rights of others. Finally, the deleterious effects of prohibiting the wearing of a kirpan outweighed the salutary effects such that this infringement was not justifiable in a free and democratic society.

An identical result was held in the case of a mature 14 year old Jehovah witness girl with Crohn’s disease and serious dilution of hemoglobin after initial treatment with IV fluids, refusing a blood transfusion for religious reasons, which was administered under Court order at the request of the Director under the Manitoba Child and Family Services Act. In Manitoba (Director of Child & Family Services) v. C. (A.), [2009] 2 S.C.R. 181 the Court found:

“The limit on religious practice imposed by the legislation emerges as justified under s. 1”.

The Canadian Charter promotes the active engagement of diversity in religious views, the promotion and respect of all religious views in relationship to one another; it promotes religious pluralism, rather than relativism or syncretism. Its protection of conscience and religion it is both individual and collective in nature, not based upon an expressed separation of Church and state, and plural in experience and intent. It recognizes a broad definition of both religion and freedom of religion, and places particular emphasis on the protection of the minority with respect to religious rights. However, freedom of religion in Canada is not absolute. It is subject to justification, in that rights may be infringed where that infringement is pressing and substantial, rationally connected to a legitimate objective, minimally impairs the rights of those which it adversely affects, and where the salutary effects of the breach of rights outweigh the deleterious effects. In this very Canadian way, the individualistic protection of rights in the Charter is balanced by the traditional communal, pluralistic values of the Canadian Constitution.

- Details

- Written by Kevin P. Feehan

- Category: Legal

This article was originally published in the Fall 2015 issue of The Catholic Dimension, and is re-posted here for public reference.

It is generally understood that publically-funded separate Catholic education is constitutionally guaranteed in the Province of Alberta. What is less well understood is the qualitative nature of that protection. Critics of separate Catholic education may be heard to express the opinion that although Catholic education is guaranteed constitutionally, there is no need to put flesh on those bones; that is, there is no need to support it fully and substantively in terms of full and equitable funding, school buildings, maintenance and control over policy, procedure and governance, the right to preferential hiring, promotion and discipline for denominational cause, and the right for Catholic theology, philosophy and doctrine to be fully permeated in all aspects of Catholic schools. The intent of this article is to explore the doctrines of hollow rights and permeation, as some of the constitutional underpinning of the qualitative protection of separate Catholic education in Alberta.

The Constitutional Guarantee

As indicated above, most persons understand the constitutional guarantee of publically-funded separate Catholic education in the province of Alberta.

The Constitution Act, 1867 was negotiated by the fathers of confederation at the Charlottetown Conference of 1864, the Quebec Conference of 1866, and the London Conference of 1867. It is universally understood that Confederation could not have been achieved without protection for denominational education in the new Canada, protection for the rights of Protestant education in the province of Quebec and Catholic education in the Province of Ontario.

The result was an historical compromise. Powers allocated to the federal government were set out in section 91 of the Constitution Act, 1867, and to the provinces in section 92. However, because protection for denominational education was so critical to being able to reach a constitutional compromise, it was set out in a separate section, section 93 of the Act:

“93. In and for each Province the Legislature may exclusively make Laws in relation to Education, subject and according to the following provisions:

(1) Nothing in any such Law shall prejudicially affect any Right or Privilege with respect to Denominational Schools which any Class of Persons have by Law in the Province at the Union;”.

The most often quoted excerpt to this effect is the speech in the House of Commons of Prime Minister Sir Charles Tupper in 1896 when he said:

“… but for assent that in the Confederation Act should be embodied a clause which would protect the rights of minorities, whether Catholic or Protestant, in this country, there would have been no confederation …”.

The issue of denominational education was also central to the entry of Alberta and Saskatchewan into confederation in 1905, and the subject of intense debate and negotiation. Section 17 of the Alberta Act, 1905 and the Saskatchewan Act, 1905 are identical:

“17. (1) Section 93 of The British North America Act, 1867, shall apply to the said province, with the substitution for paragraph (1) of the said section 93, of the following paragraph:--

1. ‘Nothing in any such law shall prejudicially affect any right or privilege with respect to separate schools which any class of persons have at the date of the passing of this Act, under the terms of chapters 29 and 30 of the Ordinances of the North-West Territories, passed in the year 1901, or with respect to religious instruction in any public or separate school as provided for in the said ordinances.’

2. In the appropriation by the Legislature or distribution by the Government of the province of any moneys for the support of schools organized and carried on in accordance with the said chapter 29 or any Act passed in amendment thereof, or in substitution therefor, there shall be no discrimination against schools of any class described in the said chapter 29.”

Eleven versions of that section were debated, amended and re-amended in months of debate. The primary actors in the Autonomy Debates and what has been called the North-West Schools Question where Prime Minister Sir Wilfred Laurier, Justice Minister Sir Charles Fitzpatrick and Minister of the Interior, Sir Clifford Sifton, all of whom considered those provisions to be a compromise for the purpose of allowing Alberta and Saskatchewan to come into Confederation. Sir Clifford Sifton is reported to have characterized any failure to reach such a compromise as potentially leading to “a complete smash-up followed up by dissolution and the recasting of the parties on religious and racial lines.”

The constitutional primacy of these denominational education protections was affirmed in section 29 of The Charter of Rights and Freedoms:

“29. Nothing in this Charter abrogates or derogates from any rights or privileges guaranteed by or under the Constitution of Canada in respect of denominational, separate or dissentient schools.”

The Government of Canada publication: “The Charter of Rights and Freedoms: A Guide for Canadians” explains that these denominational school rights cannot be overcome by reference to other sections of the Charter nor by other quasi-constitution legislation such as the Alberta Bill of Rights or the Alberta Human Rights Act:

“The establishment and operation of religious schools will not be adversely affected by any other provisions of the Charter.

This insures, for example, that neither the freedom of conscience and religion clause nor the equality rights clause, will be interpreted so as to strike down existing constitutional rights respecting the establishment and state financing of schools operated on a religious basis, with students and teachers selected according to their adherence to a particular religious faith.”

The Hollow Rights Doctrine

It is an important doctrine of constitutional law that constitutional rights once granted must not be minimalized nor diminished to “hollow rights”. They must, in all interpretations, be given a large, liberal interpretation. The Supreme Court of Canada in the Bill 30 case (1987) said that separate school rights cannot be interpreted as “an empty shell”, or “illusory (so that) the purpose of the Imperial Legislation is subverted”. Additionally, the Court said in the Ontario Home Builders case (1996) that it is critical the constitutional right “protect the substance of the guarantee”, and not be “stereotyped” at the date of entry into confederation nor “frozen in time”. Additionally, the Court has said in numerous cases including Hirsch v. Montreal Protestant School Commissioners (1926), Greater Montreal Protestant School Board (1989), Ontario Home Builders’ Association (1996), Bill 30 (1987), Reference re: Education Act (Quebec), (1993) and Greater Hull School Board (1984) that in order to avoid the error of making constitutional rights “hollow”, denominational school rights must include “non-denominational rights necessary to give effect to denominational protections”, including “exclusive control of finances and pedagogy”.

Clearly, separate Catholic educational rights must be allowed an expansive and generous interpretation in order to breathe life into the constitutional compromise on which Canada was founded.

The Doctrine of Permeation

In the Moose Jaw School case (1974) the Saskatchewan Courts affirmed “that Roman Catholics expect that religion will permeate a Roman Catholic school system in all its relationships”. The doctrine of permeation was explored at length in Public School Boards Association of Alberta v. Alberta (1996) by Dr. Nick Kach who testified that education in Catholic separate schools prior to 1905 was conducted on an “infusion” or “permeation” basis whereby the religious or denominational aspects of the Catholic faith were “infused into or permeated every subject taught during the school day, from opening prayer through all academic classes”. The philosopher Van Cleave Morris set out that philosophy of permeation:

“It appears, for example, in the affairs of the playground, in the kind of sports that are favoured and opposed, and in the code of sportsmanship by which the young are taught to govern their behaviour. It appears in the school’s definition of the delinquent and in its mode of dealing with him …. it appears in the department of science: in the methods the young are expected to adopt in conducting their experiments …. it appears in the department of social studies: in the problems that are chosen … in the manner in which they are discussed …. it appears in the department of literature: in the novels, the poems, the dramas that are chosen for study, in what is considered good and what is considered bad …. it appears in the organization and the government of the school …. it appears in the program for the general assemblies of the schools: in the various leaders from the community …. it appears in the way the community organizes to conduct its schools: and the provision it makes in its school grounds, buildings, and equipment, and the kind of people it chooses to serve on the school board, and in the relation of the members of the board to the … teaching staff”.

The doctrine that Catholic schools are entitled to permeate Catholicity, Catholic teaching and Catholic dogma in all aspects of its curriculum was specifically recognized by the Supreme Court of Canada in Hirsch (1926), Greater Hull (1984), Greater Montreal (1989) and Mahé (1990), where the Courts recognized that Catholic parents would be entitled to permeate their religion in their school system by exclusive control of pedagogy, exclusive control of maintenance and support of the system, the power to hire, promote, and fire teachers on denominational grounds, and the “exclusive management and control of all aspects of the educational system”.

In Conclusion

It is clear that publically-funded separate Catholic education is here to stay. It is constitutionally protected not only in form but in content and quality. Separate Catholic education is constitutionally protected in its own right, cannot be challenged by reference to the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Alberta Bill of Rights or the Alberta Human Rights Act, and includes full management and control of the school system including full permeation of Catholicity in every aspect of the system, management and control by Catholic parents, exclusive control over pedagogy, and the right to full permeation of Catholic philosophy and theology across the system. Those rights cannot be interpreted as “hollow rights” and must be given a full, broad and liberal interpretation so as to reflect the fundamental constitutional compromise upon which this country was founded. Catholic denominational school rights are more than formalistic; they are living, breathing and growing in the understanding of the Gospel and the teachings of the Catholic Church.

Hollow Rights and Permeation...

- Details

- Written by Kevin P. Feehan

- Category: Legal

This article was originally published in the Spring 2001 issue of The Catholic Dimension, and is re-posted here for public reference.

It is easy to take for granted that we have Catholic School Boards in Alberta, that we elect Catholic Trustees to those Boards and that they operate Catholic schools to be attended by our children. However, we often do not pause to ask the question: What makes our Catholic schools Catholic?

Why can't a Public School Board simply open a school and say that it is a Catholic school? Why can't a Public school simply open a classroom at the end of the hallway and call it a Catholic classroom? Why can't a joint Board of Trustees operate some schools which are called Catholic and some schools which are called Public?

In 2000, we had the rare opportunity to explore these questions in the context of exploring Francophone governance, 4 x 4 expansion and joint facilities issues in Alberta. We also had the rare opportunity to have legal affidavits sworn, directly addressing these questions by His Grace Thomas Collins, Archbishop of Edmonton, and His Excellency Frederick Henry, Bishop of Calgary.

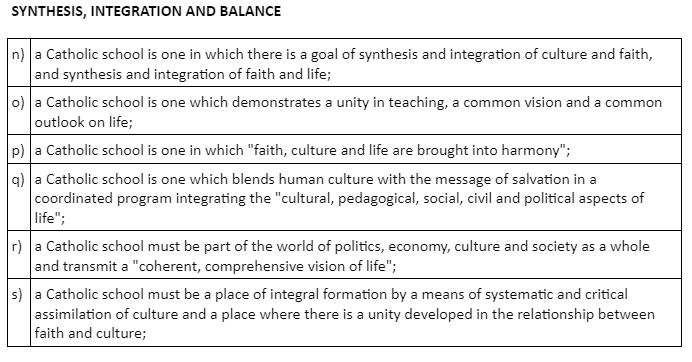

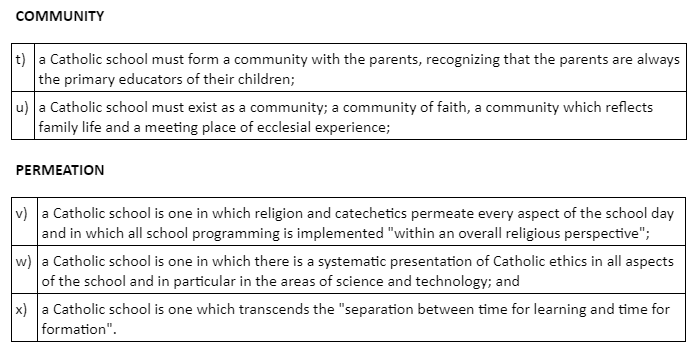

Archbishop Collins, in his affidavit, referenced the teachings of Vatican II, the Code of Canon Law, publications of the Congregation for Catholic Education, an address by Pope John Paul II and an article by American Archbishop Pilarczyk entitled "What is a Catholic School?" and said the following which is set out in full:

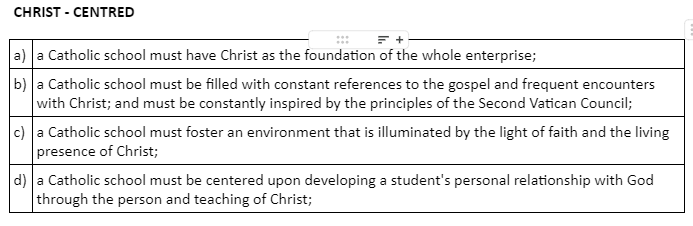

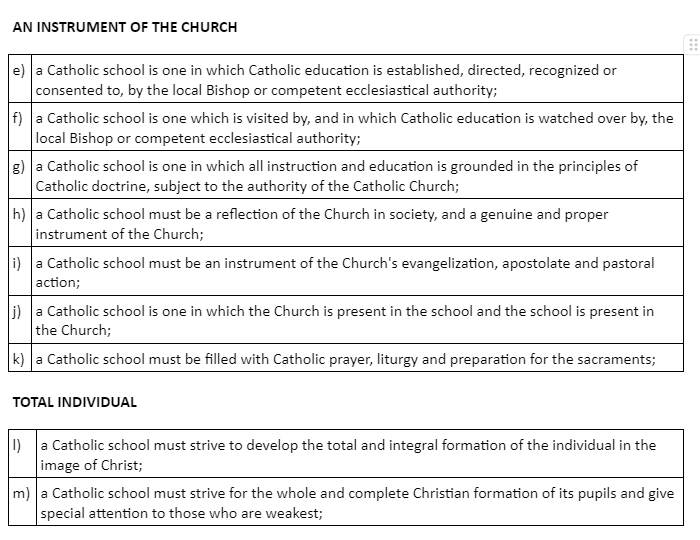

1. After review of the above documents, I believe that there are some essential principles which describe a Catholic school, including but not limited to the following:

Bishop Henry supplements Archbishop Collins' listing of the indicia of Catholic education by saying that a Catholic school must "offer instruction in the Catholic faith,... (and) participate in Catholic liturgical celebrations and sacraments in their schools without violation of Catholic faith principles". Bishop Henry also emphasizes that "in the Catholic Separate Schools in Alberta, there is a critical tripartite relationship between the parents, Catholic schools and the Catholic parish churches, each playing a vital role in the whole education of children in Catholic schools." He advises that the foundation for Catholic education is the existence of a separate "duly elected and accountable denominational school board" where "trustees are elected by majority vote of Catholic ratepayers in each separate school district" and where those Catholic school trustees "have the constitutional, statutory, moral and religious duty to preserve and enhance Catholic education for the benefit of all children attending Catholic schools."

It is the responsibility of every Catholic elector to ask the critical question: "What makes a Catholic school Catholic?" It is then the responsibility of every Catholic elector to review the structure, organization and delivery of education in their own jurisdiction and answer that question for themselves: are we providing a truly Catholic separate education to our children?

- Details

- Written by Kevin P. Feehan

- Category: Legal

This article was originally published in the Spring 2000 issue of The Catholic Dimension, and is re-posted here for public reference.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms

The Constitutional enactment which brought Alberta into confederation was the Alberta Act, 1905. Section 17 of that Act, section 93 of the Constitution Act 1867 and sections 41 to 45 of the Northwest Territories School Ordinance 1901, guarantee Catholic ratepayers the right to establish a separate school district, set assessments, collect taxes, permeate Catholicism in all aspects of education and enjoy all the rights, powers, privileges allowed to public school districts.

A history older than Alberta

On July 15, 1870, Canada assumed Rupert's Land from the Hudson's Bay Company, effectively gaining control over education in what is now Alberta and Saskatchewan. In 1875, the first North-West Territories Act was passed. Section 11, entitled public and separate school jurisdictions to establish. There were no restrictions on the geography of those school jurisdictions.

In 1884, the School Ordinance provide that a public or separate school district "comprise an area of not more than 36 square miles" (a 6x6). Separate school districts were not bound by the geography of public school districts. In addition, public or separate school districts could be expanded at the request of landowners. Under the School Ordinance of 1884, four Catholic Public boards (Fort Saskatchewan, St. Albert, St. Leon and Cunningham) and three Catholic Separate boards (Calgary, St. Joachim's (now Edmonton) and Bellerose) were established.

By 1886, the formation of separate districts was restricted to the boundaries of public school districts established on a 6x6 basis, and in 1887, the formation area for public districts, and therefore separate districts, was reduced to twenty five square miles (a 5x5).

By 1901, a separate school district could be established within the boundaries of any public school district established without reference to specific geography (1875-1884), on a 6x6 basis (1884-1887), on a 5x5 basis (1887-1901), or on any other basis allowed in the discretion of the Minister subject to protection of separate school constitutional rights. It was this right of establishment that was constitutionally protected in the Alberta Act, 1905.

Then, in 1913 the basic geography of a school district was again reduced, this time to a 4x4 area.

The 4x4: wrong assumption

For reasons unknown, it became assumed after 1913 that Catholic school districts could only be formed on the basis of 4x4s. This assumption persisted, despite the continuing evolution of public school geography.

In 1913, the Minister was enabled to create public consolidated school districts no longer bound by the 4x4 geographical jurisdictions. In 1916, the Minister was authorized to organize "any portion of the province into a district", so that districts could now be of any size or dimension. By 1919 consolidated school districts were allowed to include any territory of not less than 30 and not more than 80 square miles.

The first Schools Act of Alberta was passed in 1922. This Act recognized basic 4x4 school districts, larger basic school districts "in special cases", consolidated school districts and secondary consolidated school districts. In 1931, a new type of district was added to the jurisdictional list, the "rural high school district".

In 1966, the qualifying boundaries for school districts and consolidated school districts were repealed so the public school districts and consolidated school districts could be established without restriction as to geography. In 1970, the Minister was entitled to establish divisions of any number of public school districts.

In 1988, the Minister was confirmed in the right to establish any portion of Alberta as a public school district, or to establish divisions consisting of any number of public school districts. A separate school district could be established within a public school district and the Minister could by order add land to, or take land from, a district or division, or divide a district or division into two or more districts or divisions. There were no references in this act to specific geographical dimensions for districts or consolidated districts, as those references had been deleted in 1966.

Finally, recent legislative amendments, while preserving all of the above jurisdictions, added the concept of a regional division, either formed on a voluntary basis (School Amendment Act 1993) or forced basis (School Amendment Act 1994).

The 4x4: no foundations in law

There is no foundation in law to require separate school districts to be formed on a 4x4 basis.

Separate School districts were entitled to form between 1875 and 1884 without reference to specific geography; between 1884 and 1887 on the basis of 6x6 jurisdictions, but separate school districts need not have been based upon public school districts; from 1887 to 1913 on the basis of 5x5 jurisdictions; from 1913 to 1966 on the basis of 4x4 jurisdictions, and without restriction as to specific geography from 1966 to present. Yet, the practice continues; the Catholic ratepayer is legally and administratively directed to do just that.

There is no foundation in law for restricting separate school jurisdictions to the original 6x6/5x5 or 4x4 public school jurisdictions.

Public school districts were not limited to such original geographical restrictions. They included, beginning in 1913, consolidated school districts which by 1919 could be of no less than 30 square miles nor more than 80 square miles; from 1922, secondary consolidated school districts; from 1931, rural high school districts; and from 1970, regional districts. Even these larger jurisdictional areas became artificial, being subject to orders of the Minister adding land to, taking land from, conjoining districts, separating districts and otherwise altering the basic shape, configuration and size of these geographical areas. In addition, the Minister always had power and authority to create school jurisdictions without reference to specific geographical boundaries, subject only to the constitutional rights of separate school ratepayers.

There is no foundation in law for restricting formation of separate schools to the geography of public school districts, even including larger district jurisdictions.

The Supreme Court of Canada has made it quite clear that protection of minority educational rights is "itself an independent principle underlying our constitutional order" (the Quebec Secession case, 1998), that educational rights cannot be stereotyped by the type of educational jurisdictions and rights existing at confederation (in the case of Alberta; 1905) (Hirsch v. Montreal Protestant School Commissioners (1928), Greater Montreal Protestant School Board v. The Attorney General of Quebec et al (1989) and Reference re: Education Act (Quebec) (1993)). Likewise, separate school constitutional rights cannot be confined to literal wordings or stereotyped to avoid the purpose and intent of the protection of minority rights (Greater Montreal Protestant School Board v. The Attorney General of Quebec et al (1989), Ontario Home Builders' Assn. v. York Region Board of Education (1996)). Finally, the Supreme Court of Canada has said many times that the constitutional rights of separate school supporters cannot be restrictively interpreted so that they are "hollow rights" which cannot be effectively exercised in the modern context (Reference re: Bill 30 (1987), Attorney General of Quebec v. Greater Hull School board (1984), Greater Montreal Protestant School Board v. The Attorney General of Quebec et al (1989), Reference re: Education Act (Quebec) (1993), Ontario Homes Builders' Assn. v. York region Board of Education (1996)).

Hollow rights wholly illusory

To restrict separate school formation to the archaic boundaries of 6x6s, 5x5s or 4x4s, or even to the larger unified boundaries of consolidated school districts, secondary consolidated school districts, rural high school districts or regional districts, when public school jurisdictions are now comprised of divisions and regional divisions, is only to accord separate school supporters "hollow rights" which are "wholly illusory" with respect to the formation of their districts.

Constitutional protection

It was the intent, purpose and substance of constitutional protection that separate school supporters would be entitled to establish separate school jurisdictions in any area of the province of Alberta which was established and organized for public school purposes.

This purposive interpretation is not to be limited by archaic geographical boundaries.

The challenge

The challenge for Catholic schools now is formation or expansion on geographical areas unfettered by 86 years of administering the 4x4 assumption in Alberta. Perhaps we should envision coterminous boundaries with public school divisions or wards of public school regional divisions, or creative areas for separate school expansion limited only by the needs of separate school ratepayers and students. Perhaps it is time to seize the opportunity to bring separate school education to all Catholic students in Alberta. It would not be impossible for the government to make it happen; all that is required is the political will.

- Details

- Written by Kevin P. Feehan

- Category: Legal

This article was originally published in the Fall 2000 issue of The Catholic Dimension, and is re-posted here for public reference.

The Charter of Rights and Freedoms

In 1982, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms became law. It provided in section 23 that all citizens whose first language learned and still understood was that of the English or French linguistic minority in any Province, or who had received their primary school instruction in Canada in English or French, or whose older children had received primary or secondary school instruction in English or French, would have the right to have their children receive primary and secondary school instruction in that minority language. The right to minority language education applied whenever the number of s. 23 children were sufficient to warrant the provision to them of minority language instruction in minority language educational facilities.

In Alberta, that minority language educational protection was granted to the Francophone minority.

Before the Supreme Court: Mahe v. Alberta

In 1990, the Supreme Court of Canada heard a case from Alberta which sought to determine whether the right to minority language education, where numbers warranted, included the right to "management and control" over minority language facilities and instruction. Mahe and others argued that the establishment by the Edmonton Catholic Board of a Francophone school, Maurice Lavallee, was not sufficient to satisfy section 23 Francophone education rights. They argued that the Francophone community should be entitled to establish a school board by which "management and control" of French language schools would be accorded directly to the Francophone parents in Edmonton.

The Supreme Court of Canada ruled that the general purpose of section 23 of the Charter was to preserve and promote two official languages and two distinct cultures in Canada and to correct, on a national scale, the progressive erosion of minority official language education. The Supreme Court of Canada said that section 23 encompassed a "sliding scale" of requirements depending upon the number of students involved. They said that where numbers warranted, section 23 may require an independent Francophone school board.

On the other hand, where numbers of Francophone students were lesser, "management and control" might be satisfied by linguistic minority representation on the existing school board.

The Supreme Court of Canada determined that in the Edmonton area, there were sufficient numbers of section 23 students to justify, in both pedagogical and financial terms, the creation of an independent Francophone school. It also recognized that the creation of Francophone school boards might not be compatible with the constitutional rights enjoyed by existing Catholic school boards. It said that any interpretation of section 23 of the Charter "must be consistent with the rights and privileges of denominational schools". The protection of denominational rights consistent with Francophone educational rights would be easily accomplished where there was not a separate Francophone school board, and where members of the denominational minority were entitled to elect a person both of the denominational minority and of the linguistic minority to represent their point of view on the existing separate board. Where numbers warranted an independent school board, the Supreme Court of Canada said, "it is possible to constitute minority language boards along denominational lines."

The Supreme Court of Canada said particularly:

"I do not doubt that the rights of denominational school boards may, in some cases, result in limitations on the type of reorganization which might otherwise be required under s. 23. Denominational school guarantees could split up an eligible group of minority language students in such a way as to preclude the creation of a minority language school which would otherwise be required."

The Alberta Response: Francophone School Authorities

As a result of the Supreme Court of Canada decision in Mahe, the Province of Alberta passed amendments to the School Act, Part 8.1, providing for the creation of four non-denominational Francophone authorities in Alberta; one each for the Edmonton area, northeast, northwest and southern Alberta.

A Question of "Management and Control"

The southern Alberta Francophone authority, established on February 1, 2000, requested management and control of Ecole Ste. Marguerite-Bourgeoys in Calgary. The Calgary Catholic Board opposed transfer of the school because of their concern that the children attending the school would lose the constitutional protections of a guaranteed Catholic education. During an exchange of letters in late 1999 and early 2000, Calgary Bishop Frederick Henry expressed concern with the concept of a single or umbrella Francophone school board responsible for both public and separate Catholic Francophone governance in southern Alberta. He indicated that he would have no choice but to formally deny a school transferred to a non-denominational Francophone Authority, the status of a "Catholic school".

Edmonton Archbishop Thomas Collins stated that a unitary governance management model comprised of a single non-denominational school board, consisting of trustees and electors who are Catholic and non-Catholic, is not sufficient nor appropriate to deliver a fully-permeated Catholic education, consistent with the essential principles of Catholic education. Archbishop Collins stated that a non-denominational Francophone authority operating under a unitary governance management model could not provide a Catholic education that would meet the criteria of the Catholic Church.

There was also a concern that a non-denominational Francophone school program which was "de facto" Catholic, would be found to violate the rights of Francophone children attending the school who did not wish a fully-permeated Catholic education. Such a challenge, which could be taken under section 2(a) of the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, would be, probably, successful.

It was apparent to everyone involved that the right to provide a fully-permeated Catholic education was not constitutionally protected through a non-denominational Francophone authority.

It is clear that only denominational schools are entitled to exercise the constitutional protections accorded by section 93 of the Constitution Act, 1867 and section 17 of the Alberta Act, 1905, and more particularly, to permeate the Catholic faith in separate Catholic schools.

Fixing the Problem in the Short-Term

In June, 2000, the Calgary Catholic Board and the Southern Alberta Francophone Authority entered into an intense negotiation to work out a short-term solution in Calgary which would allow Catholic Francophone parents to provide for their children an education which was constitutionally protected both linguistically and denominationally.

On June 26, 2000, the parties signed an agreement requesting that the Minister of Learning create two new Francophone regional authorities for southern Alberta, a Separate Catholic Francophone Authority and a Public Francophone Authority, and to divide between them the existing non-denominational Francophone authority. The parties asked the Minister of Learning to appoint the existing members of the Southern Alberta Francophone Authority to the respective new boards and to set an election for September 2000 to fill the vacancies on the boards. The parties agreed that the current superintendent and secretary-treasurer of the Southern Alberta Francophone Authority would become the interim superintendent and secretary-treasurer of the Separate Catholic Francophone Authority and that the Separate Catholic Francophone Authority would enter into a contract with the Public Francophone Authority for the purpose of providing the services of the superintendent and secretary-treasurer to that authority.

The agreement between the parties provides that Calgary Catholic maintains actual and legal ownership of the school, but the funding and student count of the school becomes that of the Separate Catholic Francophone Authority. The Separate Catholic Francophone Authority would purchase from Calgary Catholic a complete education and support package, at cost, which would include administrative services, the services of the principal, teaching staff, professional support staff and support staff, for the term of the agreement. The teaching staff of the school remains the teaching staff of Calgary Catholic and the curriculum currently in place at the school would remain during the term of the agreement.

A Reconciliation Team was established to identify and address issues in the school community which were a source of division or conflict. This Team is to plan for a seamless transition and complete transfer of management and control of the school from Calgary Catholic to the Separate Catholic Francophone Authority after the issue of separate Catholic Francophone governance in Alberta is addressed in the longer term.

The Minister of Learning issued a Ministerial Order on July 7, 2000, effecting the terms of that agreement. As a result, in Calgary, in the short-term, Catholic Francophone parents are entitled to send their children to a school operated under a management structure which protects both their children's Francophone linguistic rights and Catholic denominational rights.

Fixing the Problem in the Long-Term

The parties also agreed to request that the Minister of Learning establish an investigative task force for the purpose of recommending legislative amendments to the School Act, so as to create distinct legal entities which would entrench both separate Catholic and Francophone education constitutional rights fully, so that "governance of separate schools which are both Francophone and Catholic will be granted and reserved to the Francophone Catholic community in a manner which enforces the constitution or protections of section 17 of the Alberta Act, 1905 and of section 23 of the Charter." The Catholic and Francophone communities in Alberta await the appointment of that task force by the Minister and the recommendations to amend the School Act so that all regions of Alberta will have access to education which fully protects both Francophone linguistic rights and Catholic denominational rights.

- Details

- Written by Charlotte Taillon

- Category: In The News

Two weekends ago we hosted our 2024 Catholic Education Symposium at Corpus Christi Parish in Edmonton.

Nearly 140 members of the Catholic Education community, including trustees, superintendents, principals, teachers, school chaplains, members of the clergy, and university students all joined together to discuss a vital question:

How do we support the formation of teachers in our schools so that they can serve as faithful Catholic witnesses for our school and model for our students?